ALONZO HOWARD

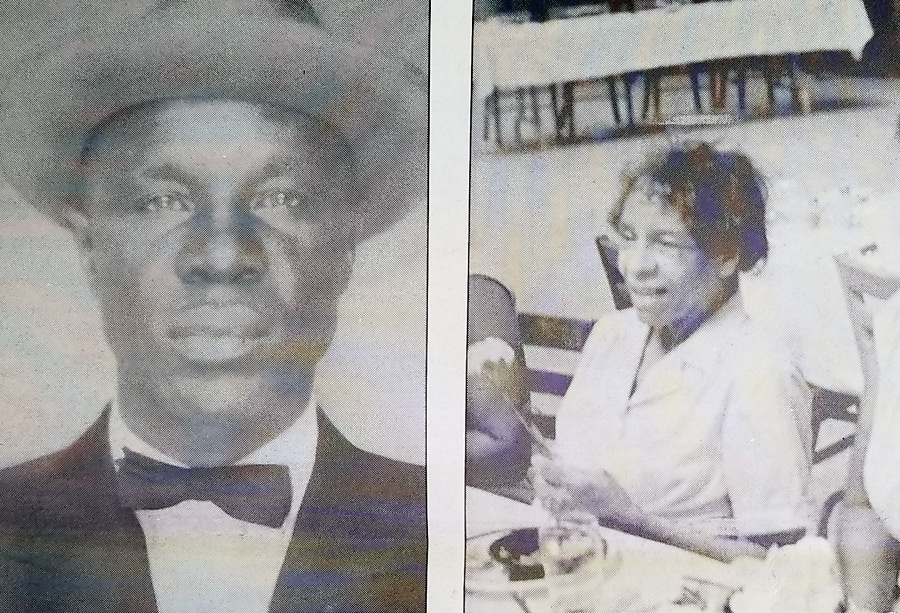

Alonzo Howard and wife Annie Lee.

Alonzo Howard and wife Annie Lee.

Alonzo Howard and Annie Lee Phelps met at a church picnic in the early 1900s. As she would tell her children years later, Alonzo was a sporty and dapper man, a good dresser who wore a straw hat. She was a woman of café-au-lait coloring, a little shy, perhaps a little proud. He was nut brown, the dark color of his African ancestors, a driven man destined to make his own way.

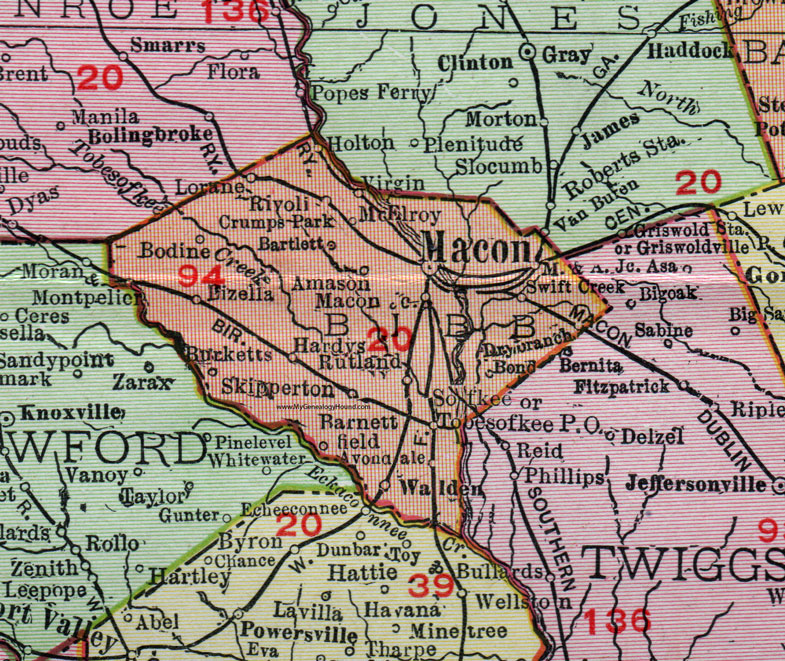

He was born on Nov. 11, 1897, according to his family. (The 1900 census listed his birthdate as October 1893.) He was born in Lorane, GA, near Bolingbroke, as shown on a 1936 death certificate for his infant son.

As Annie Lee told her children, she was born on Dec. 11, 1900, in Walden, GA, and raised in Avondale in south Bibb County. Her parents were William and Abbie Phelps. She attended public schools in Bibb County and joined Mount Zion Baptist Church at an early age.

The 1900 Census showed her birth year as 1898 and living in Rutland, Bibb County, the first born of William and Abby Felth (the Census-taker’s spelling of her parents’ names). She had at least four siblings. Her parents – listed as William Felts and Abbie Jones on their marriage certificate – were married on June 24, 1893. Her father was a farmer.

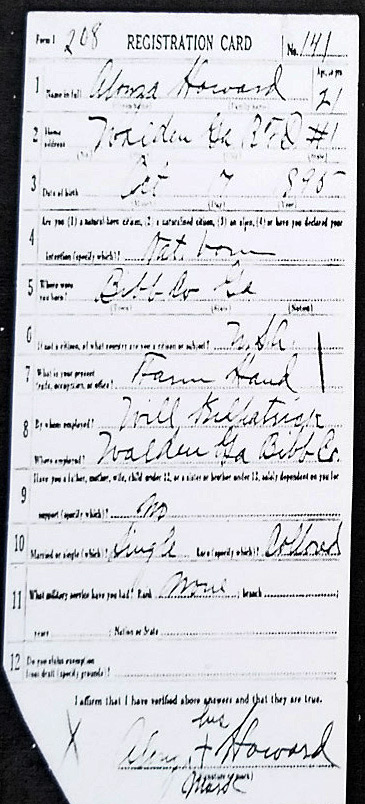

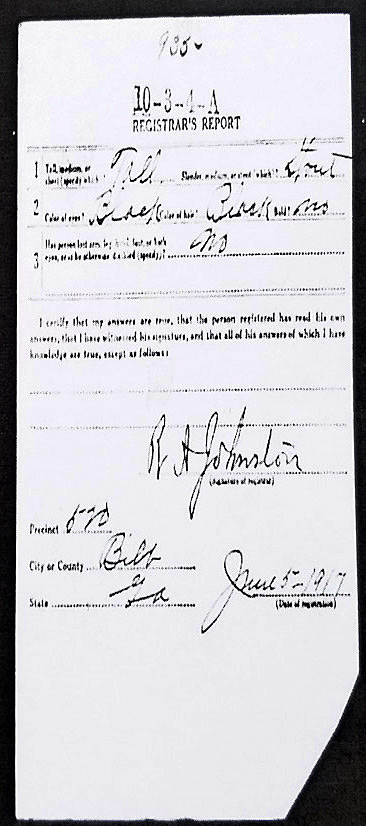

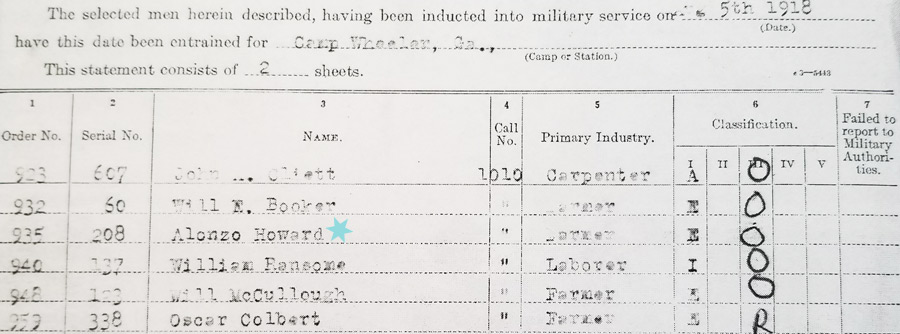

Alonzo was among the millions of men drafted into the U.S. Army under the Selective Service Act of 1917. As the country prepared for war with Germany, it sought to build up its sparse military.

Alonzo and his brothers Walter and Guss were among the men required to sign up in the first round of registrations on June 5, 1917. His brother-in-law Bailey McClendon, who had married Alonzo’s sister Irene in 1915, was among the third round of registrants, on Sept. 12, 1918.

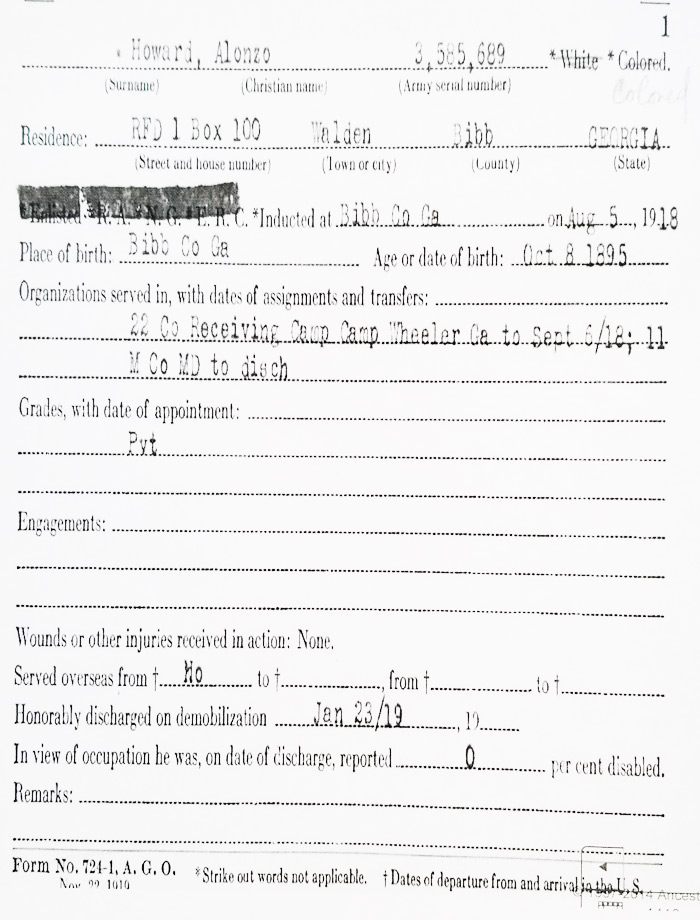

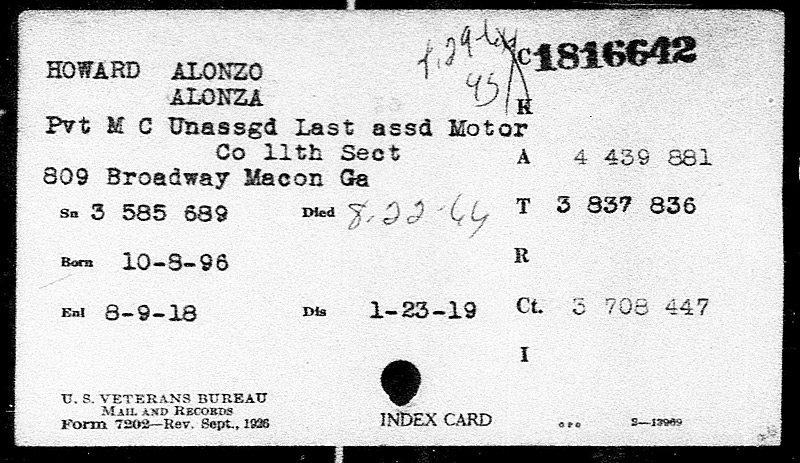

A single man, Alonzo was 21 years old when he registered (his birthdate is listed on the registration form as Oct. 17, 1895 and on discharge papers as Oct. 8, 1895). In August 1918, he was inducted into the segregated Army into the 22nd Company at Camp Wheeler, just outside Macon, Ga, until Sept. 6, 1918. He was discharged as a private on Jan. 23, 1919. The camp officially closed in April 1919, five months after the war ended.

Alonzo was stationed at the Camp Wheeler Army base outside Macon. The location is now a historic site.

Alonzo was stationed at the Camp Wheeler Army base outside Macon. The location is now a historic site.

Alonzo was listed as a farm hand employed by Will Kilpatrick. He was described as a “colored” man who was tall, stout, with black eyes and hair.

Camp Wheeler was the base for 3,000 Black soldiers constructing draining systems and repairing camp roads. Under Jim Crow laws, they trained and served under white officers.

In 1918, white farmers complained that the military was drafting too many of their Black workers. To appease them, Camp Wheeler officials allowed the soldiers to pick cotton and harvest crops on private farms.

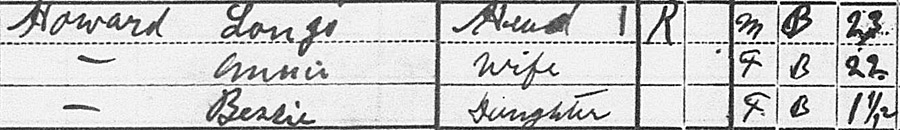

Alonzo and Annie Lee married on Dec. 26, 1917, when she was 17 years old. Their names on the marriage certificate were Lonza Howard and Anna Lee Felth.

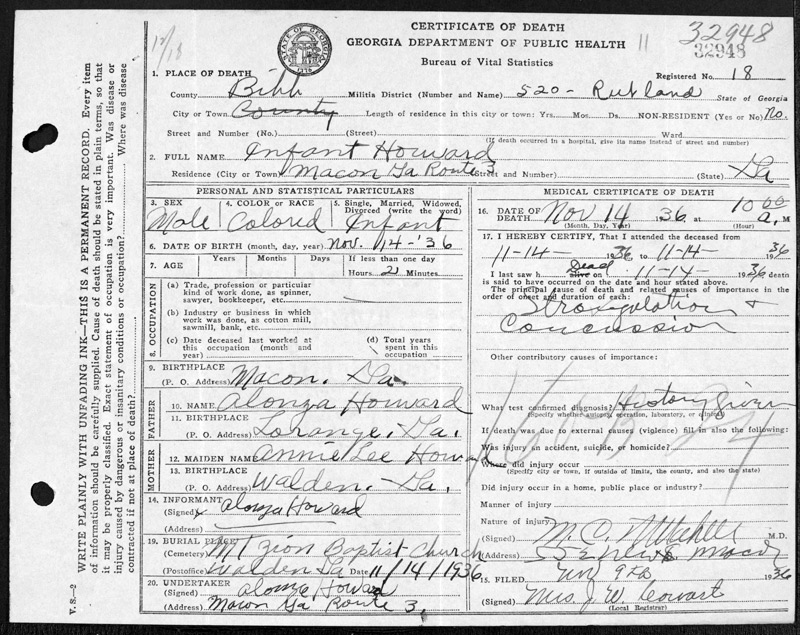

From this union came 14 children, two of whom died in childbirth. A son, whom daughter Abbie Lee Howard recalled was named after his father, died shortly after birth in 1936, according to his death certificate.

Of the 12 who lived, eight were girls – Bessie Mae, Elizabeth, Rebecca, Ceola, Lonnie Mae, Abbie Lee, Doris and Dora. The four boys were Charles (or C.W.. as he was called), Walter Green, Willie Floyd and Arthur Lee.

Their youngest daughter Dora was given the birth name Annie Lee (she appears as Anna on the 1940 Census). It was later legally changed by her mother to add the name Dora to it, Dora recalled. “Daddy had a mule named Dora. I think that’s where she got the name,” she speculated. She was not an easy child, Dora said. “I’d get mad and pull the curtains down when I didn’t get my way.”

Alonzo, Annie Lee and the children lived in Rutland/Avondale in Bibb County, according to the 1920, 1930 and 1940 Censuses. They did not live far from Mount Zion, where they were faithful members.

Following their family tradition, he became a farmer and she became a farmer’s wife. During the 30 or more years the family lived in Avondale and Skipperton, Alonzo presumably worked on a white man’s property, all the time saving money to buy his own farm.

The children worked side by side in the fields with their father, playing and singing some of the time and working most of the time. Around midday, their mother brought food to the field and spread out a large meal under a giant shade tree, Abbie Lee recalled.

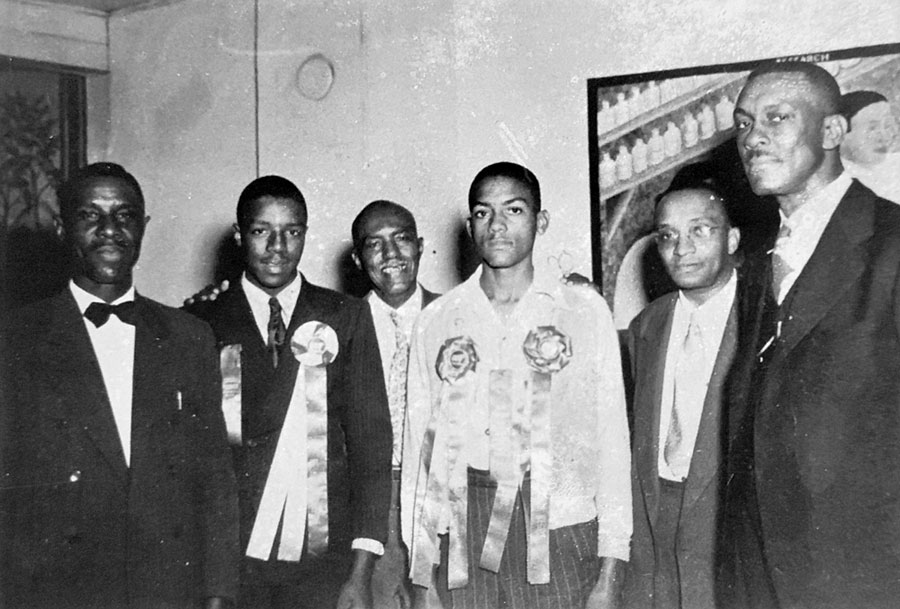

Alonzo (left) and son Walter (next to him) at what appears to be a Future Farmers of America event.

Alonzo (left) and son Walter (next to him) at what appears to be a Future Farmers of America event.

The work got to be too much for one son, Charles, who with a friend hitchhiked to Cincinnati and then to Detroit where his aunts and uncles lived.

Their father farmed hard and did quite well at it. They lived in a house with three bedrooms, a kitchen, living room and what one daughter remembered as a dining room. At one point, Alonzo had a Model T Ford.

The children attended a one-room school named Bessie Capel, which was about 1 1/2 miles from their home. They walked together to school, sometimes in the cold and rain. “After school, we changed clothes and went to the fields,” said Lonnie Mae. Abbie Lee recalled that Lonnie Mae enjoyed plowing with their father in the fields while the other children did not like farming.

Every Friday, Alonzo took his crops to the market and the children sometimes went with him. Their uncle Obie Howard and other farmers were also there.

“He would go to this place and buy peppermint candy, a big bag for a quarter (for us),” said his daughter Abbie Lee. “He’d buy peppermint candy, cheese and fish. He loved cheese and fish.”

The children remembered a mother and father who wanted their children to be useful and to learn to do things for themselves. Their father grew his own sugarcane and made syrup. He raised and slaughtered his own livestock, and cured the meat for long winter days and nights.

Holidays in the household were a time of warmth, joy and good cheer. Their mother spent days baking cakes and pies. The children remembered the toys on Christmas morning – nothing fancy but appreciated – and their thrill at finding a hunk missing from the cake left on a table for Santa Claus.

One of the sons, Arthur Lee, remembered his parents this way: “He was a good man. He worked us a little hard but sometimes we needed it. He was a man who saw that things got done. Daddy would sit down and have a spelling match with us and see who could out-spell the other.”

“Mama would look out for us a little more closely. She was a little softer. We got away with more things with her.”

Annie Lee was a soft-spoken woman, who loved to cook and bake – especially big Sunday meals. She always wore a hat and carried a dainty white handkerchief to church. “She’d buy handkerchiefs before she’d buy anything else,” Abbie Lee said. Alonzo, on the other hand, was a tough father.”

Annie Lee Howard and daughter Lonnie Mae Slocumb after moving to Macon. They moved to the city in the late 1960s.

Annie Lee Howard and daughter Lonnie Mae Slocumb after moving to Macon. They moved to the city in the late 1960s.

Both Alonzo and Annie Lee, who had been a Sunday school teacher, were church-going people. They took their children to Sunday School and church every Sunday. During the week, they had prayer meetings in their home. He was a deacon in the church, and she was the clerk.

He was a member of the Good Samaritan Lodge and the Central City Lodge No. 473 F.&A.A.Y. Mason. She was an Eastern Star.

While in south Bibb County, four of the daughters got married: Rebecca, Ceola, Elizabeth and Bessie Mae.

In the 1940s, the family spent some time in the community of Bellevue in Macon, where Annie Lee’s mother Abbie Phelps lived with her daughter’s family. Alonzo is listed in the Macon City Directory in 1942 as a laborer. A widow, Abbie Phelps worked as a laundress and maid during the 1940s.

“She used to be a washerwoman,” Abbie Lee recalled of her grandmother. She and her sister Lonnie Mae “sat down and played in the dirt when she was washing by the creek. The clothes would be so white. She had a big black pot with fire under it. She rubbed (the clothes) by hand.” Grandmother Abbie died in 1955, according to an obituary.

Arthur Lee remembered that he and his brothers Walter and Floyd stole their grandmother’s pipe to smoke. They were mischievous boys; some years before they had stolen their father’s vehicle for a joy ride.

In the 1950s, Alonzo moved the family from Skipperton to Lizella, GA, to a farm he had bought on land that seemed to stretch forever. It was land where he grew cotton, butterbeans and watermelons, where he built a barn and raised chickens and hogs, where nature’s bosom overflowed with tasty fruit – pecans and plums and blackberries and scuppernongs and persimmons. Cotton was the chief crop.

On that land, he built a seven-room house, where many of his grandchildren grew up. Abbie Lee recalled that her father always had money. “He bought the farm for cash. Mama said it,” she said.

As the decade progressed, “daddy had changed,” said Abbie Lee, “like he was going down, like he was tired.” By then, Alonzo was in his 60s and had endured the hard life of farming, raising children and rabid discrimination.

In the early 1960s, when money became scarce, Annie Lee worked as a domestic for a white family.

When the boys got older, they moved away. Walter and Floyd joined Rebecca and her husband Broadus Spivey in Cincinnati, where they moved to after his mother died in Macon. Arthur Lee went north for a while but returned, he said, because the winters were too cold.

Alonzo would not allow the girls to leave. “Daddy wouldn’t let us leave home,” said Lonnie Mae, who married Matt Slocumb in 1956. “He was tight on us. We went to church and back home.”

For most of the 1950s and 1960s, Annie Lee spent the days taking care of her grandchildren while their mothers worked, along with tending the house. Her grandchildren remember Big Mama – as she was called – as a strict woman, never allowing them out of her sight and making sure they behaved. She was their second mother, cooking their food, wiping their noses, changing their diapers and whipping their fannies.

“She was a strong woman,” said her granddaughter Sherry Lee Howard, Abbie Lee’s daughter. “But as a child, I never thought about her strength. I just knew that she was the one who would never let us do much.

“Now I see how she almost singlehandedly raised me, my sisters and brothers and my cousins while our mamas worked. How many women could do that now? I hope she always knew how much we loved her for it, even though as kids we never really thought about it.”

In the late 1950s as Alonzo got older – and his now-grown children showed little interest in continuing the farm – he grew fewer and fewer crops and the fields that had once been bountiful were becoming barren.

He had a stroke in 1964. For several years, he was a patient at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Dublin, GA. Annie Lee dutifully and regularly rode a Trailways bus for the hour-long trip to the hospital, sitting with him, letting him know that she cared.

Annie Lee Howard (third from right) with her grandson and children. From left, grandson Ronald Spivey, his mother Rebecca, Abbie Lee Howard, Arthur Lee Howard, Floyd Howard and Lonnie Mae Slocumb. They were attending the Howard Family’s second reunion in 1981.

Annie Lee Howard (third from right) with her grandson and children. From left, grandson Ronald Spivey, his mother Rebecca, Abbie Lee Howard, Arthur Lee Howard, Floyd Howard and Lonnie Mae Slocumb. They were attending the Howard Family’s second reunion in 1981.

On Aug. 22, 1966, as the family was preparing for a visit from Cincinnati relatives, the hospital called around mid-morning to say that he had died. Annie Lee was on her way to the hospital on a bus at the time. It was a sad day.

Over the years, the farm and property slipped out of the hands of the family. The Middle Georgia Girl Scouts bought part of it for a camp for Black girls and named it after a Black woman, Sarah Bailey, who organized the first group of Black girl scouts in 1945.

The council had tried to buy the property from Annie Lee but learned that she no longer owned it. The property had never been secured by Alonzo’s children. It was among the many family-owned Black farms that were lost in the early 20th century, and one that Alonzo had valiantly bought and paid for through hard work.

About two years after Alonzo’s death, Annie Lee, her remaining children and grandchildren moved to Macon, GA. She moved in with her daughter Doris and her children. She still went to church every Sunday.

Around 1975, Annie Lee slipped in her home and broke her leg. She moved around with a walker, and when she could, she went to church. Being a proud woman, she was a little embarrassed about having to use a walker, but she put her pride aside when it came to church. It was her Rock of Gibraltar.

She slipped at home a second time and her health began to fail. She had a light stroke, got better and then another. She never wanted to go into the hospital. She didn’t like them.

During the early 1980s, she had several strokes and a mild heart attack, and had to be placed in a nursing home for care. She outlived Alonzo by almost 16 years, dying on Feb. 9, 1982.

Alonzo’s Army registration document, 1917, page 1.

Alonzo’s Army registration document, 1917, page 2.

__________________________________________________________

Alonzo’s Camp Wheeler assignment papers, 1918.

Alonzo’s Camp Wheeler assignment papers, 1918.

__________________________________________________________

Alonzo’s Army discharge papers, 1919.

Alonzo’s Army discharge papers, 1919.

__________________________________________________________

Death certificate for Alonzo and Annie Lee’s infant child who died in 1936 shortly after birth.

Death certificate for Alonzo and Annie Lee’s infant child who died in 1936 shortly after birth.

__________________________________________________________

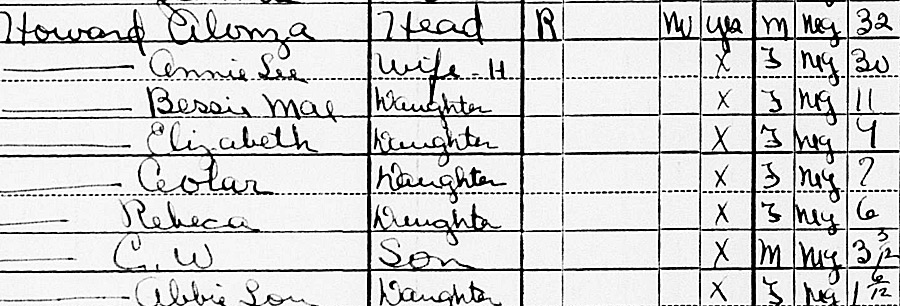

Alonzo and Annie Lee with daughter Bessie as recorded in the 1920 Census.

Alonzo and Annie Lee with daughter Bessie as recorded in the 1920 Census.

__________________________________________________________

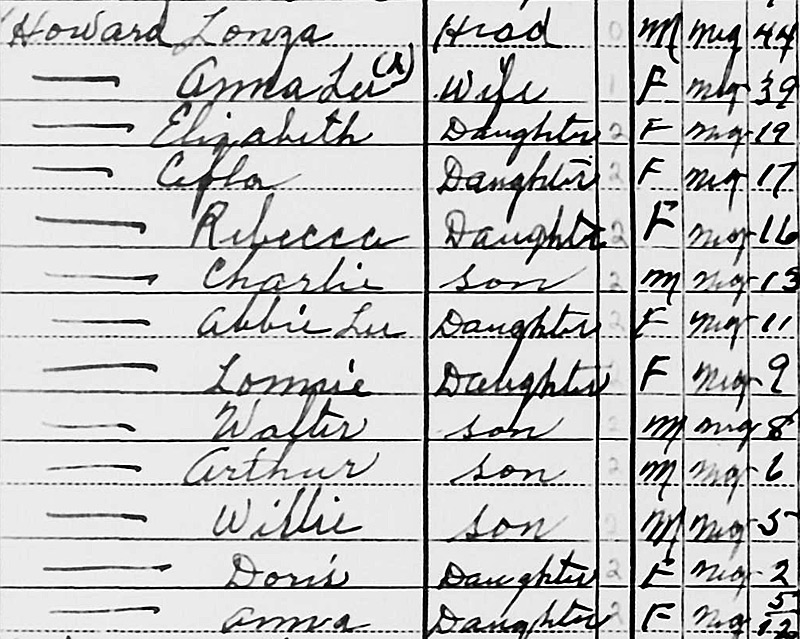

Alonzo, Annie Lee and their children as recorded in the 1930 Census.

Alonzo, Annie Lee and their children as recorded in the 1930 Census.

__________________________________________________________

Alonzo, Annie Lee and their children as recorded in the 1940 Census.

Alonzo, Annie Lee and their children as recorded in the 1940 Census.

_______________________________________________________

Alonzo’s Veteran Bureau’s card showing dates of birth and death, Aug. 22, 1966.

Alonzo’s Veteran Bureau’s card showing dates of birth and death, Aug. 22, 1966.

__________________________________________________________

1911 Rand McNally map showing some of the places where Alonzo, Annie Lee and their family lived.

1911 Rand McNally map showing some of the places where Alonzo, Annie Lee and their family lived.